I hear it all the time. We’re losing our tail on this product. Should we kill it? The question is well-intended, but often the analysis that leads to the answer is misguided. Companies that rely on standard cost systems to understand product costs, which is the vast majority of manufacturers, can easily fall victim to the trap set by this costing system.

A typical scenario goes like this:

- Management asks for a list of products sorted by margin percent.

- They draw the line at a certain margin percent. Often this is a point compared to SG&A (sales, general & administrative costs). If SG&A is 18% of sales, the logic is that any product with a margin below 18% is “losing money” because it isn’t bringing in enough margin to even pay for the overheads of SG&A.

- The company heads down a path to reduce or eliminate the low margin products, with the intention that the average margin percent should increase since they are no longer dragged down by the low margin products. They may try the direct approach and just tell customers that they are no longer going to produce a product, or they may increase the price substantially. Of course, the price increase irritates the customer, and they go shopping for alternative suppliers.

- After a few months of this, profitability is sinking. Sure, the individual product margins are higher, but the company as a whole is less profitable.

So what is happening? The underlying issue is that standard costing treats overhead costs as if they are variable. The factory overheads get applied to individual products based on an arbitrary formula like labor hour or machine hours, and those two things may have little to nothing to do with how much overhead they actually consume.

The inclusion of overhead costs into the standard cost system implies that the overhead costs that were part of the product cost must also be eliminated when the product is discontinued – just to stay even.

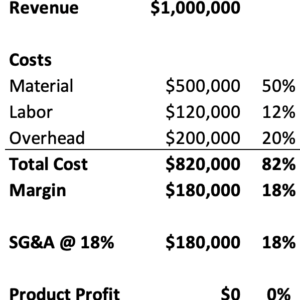

Let’s work through an example to make it real. A company has a high-volume product family that generates $1 million in revenue, but the margin is skinny at 18%. Here are the facts about this product line:

Based on this data, the product appears to produce zero profits, and therefore the leadership team decides to discontinue making it.

OK, now that that decision is made, what costs go away?

Materials – that was easy. We don’t have to buy the raw materials for this product anymore.

Labor – they have $120,000 of labor cost, so let’s call it four people. Maybe they can all be laid off, but perhaps not. One person may be needed to run another product line, and another might be close to retirement, and it doesn’t feel right to let them go. Maybe some of them are welders or machinists, and given that they are so hard to hire, we hate to let them go. However, for the sake of this exercise, let’s assume that all of these people and their costs go away.

Overhead – there is $200,000 of overhead buried in the cost of this product. How much of that can go away? Maybe a quality tech or a scheduler? Maybe? Usually, the answer is that none of these costs go away.

So, after removing this unprofitable product line, we are left with $380,000 of costs that aren’t being paid for by this product line. ($380,000 is the sum of the manufacturing overhead and the SG&A that was this product’s “fair share” of the SG&A)

By eliminating this no-profit product, profitability decreased by $380,000!

When it comes to product rationalization or even make-buy analysis, we need to look beyond standard margins to make the right decision. We need to ask questions like:

- How much does this product contribute in terms of margin dollars? I prefer to use value-add analysis, which is revenue minus materials, and other costs that would clearly go away if you didn’t make the product. Examples might be freight or sales commissions.

- Does the project need a lot of administrative support, or does it run seamlessly and effortlessly – lights out.

- If you didn’t have the project, could you refill the production capacity with other new projects at better margins?

- Practically, what costs would you eliminate if you didn’t produce this product anymore?

I think it’s healthy to review products and profitability occasionally just to make sure that something hasn’t devolved into unhealthy territory. However, the analysis that needs to be done must move beyond a standard-costing margin approach.

In my next blog I’ll address the other end of the spectrum – those high-margin, low-volume products. Again, standard cost may be painting a very inaccurate picture.

If you’d like to discuss this further, please reach out to me:

Phone: 651-398-9280

Email: rob@robtracy.net

Contact page: https://www.robtracy.net/contact/